- Home

- Simantel, Iris Jones

The GI Bride Page 2

The GI Bride Read online

Page 2

I knew how my family would react to my friendship with an American soldier, but how must Mum’s friend, Mrs Gradley, have felt when all three of her daughters married Americans and left England?

After I’d convinced my parents that Bob was just a lonely boy away from home for the first time, they agreed I could bring him home occasionally for Sunday tea.

Well, it wasn’t long before my family and I had fallen in love with the handsome young American soldier, and our courtship began. It quickly became apparent that our relationship was not just a passing fancy and soon Bob asked me to marry him. When I told him I couldn’t because I was only fifteen, he was angry and let me know it. About a week later, he came back to the house and said he was willing to wait for me for as long as was necessary: he loved me and would do whatever he could to ensure that we ended up together.

The original plan was for him to return to the United States and for me to join him when I was eighteen. However, knowing how miserable we would both be if we were separated, my parents reluctantly allowed us to be married. We became engaged on 5 July 1954, my sixteenth birthday, and were married on 16 October.

Within a few months of our wedding, I sailed away from England, away from my history and all I had known. Now, with the love I had always lacked, and my heart full of hope, I looked forward to a new and better life in America.

2: Voyage to America

‘Seasickness: at first, you are so sick you are afraid you will die and then you are so sick you are afraid you won’t die.’

Mark Twain

Oh, my God, if anyone had told me how ill I would be on that voyage, I might still have been an unmarried, virginal teenager. But, there I was, sixteen years old, the child-bride of an American soldier, about to sail across the Atlantic Ocean on a troop ship to a new life and an uncertain future in the United States of America.

The USS General R. E. Callan was a converted battleship. Its voyage had originated in Bremerhaven, Germany, and it was transporting GIs and their families back to the United States after their tours of duty. The lumbering vessel had none of the luxuries found on large commercial liners and, of course, everything was painted the regulation battleship grey. The gangways leading to the cabins were narrow, barely allowing room for passing. The four-berth cabins were tiny, and when I first saw where I would be living for the coming days, I could almost hear my mother saying, ‘Crikey, you can’t swing a cat in ’ere,’ and she would have been right. Dependants, and perhaps officers, were assigned to those cabins, while lower-ranking servicemen travelled, slept and ate separately, on a lower deck referred to as the hold. My cabin was equipped with two double-tiered bunks, four narrow lockers and two small washbasins set into a vanity-type counter. I shared this small space with three other women, all of them older than I was, of course.

We shoved our suitcases under the bunks, then introduced ourselves. First, there was Barbara McCarthy, who sounded posh and was very attractive; she was from Leeds.

‘How do you do?’ she said. ‘Nice to meet you.’

Blimey, I thought, she’s not going to be much fun.

Next, there was Gladys, I don’t recall her last name, but she was from the north of England and had a broad northern accent. ‘’Ow do? ’Ow are ye?’ she said, pumping my hand. Gladys was short and chubby, and had served in the British Army, which perhaps explained the manly handshake.

Last, there was an American. ‘Hi, girls,’ she drawled, in what I later learned was a Southern accent: she was from Atlanta, Georgia. I can’t remember her name but I do remember that she was pregnant and had little to do with us three English girls since she had a number of American friends on board.

We flipped a coin to see who would get which bunk. I got a lower bunk but later gave it to the American girl who, because of her pregnancy, had morning sickness.

Soon after I’d stowed away my few belongings, Bob came to find me. ‘Come on, honey, let’s check out this lovely hotel,’ he said, and hand in hand we explored the ship. First, and most important, we found the showers and toilets.

‘Good thing I brought a dressing-gown,’ I said. ‘I wouldn’t fancy walkin’ all this way in me nightie, not with all these men around.’ Next, we discovered the dining rooms, the movie theatre, then walked around the different decks. Knowing that the ship was about to set sail, we stayed on the main deck, standing at the rail, arms wrapped around each other, until my uncle, who had come to see us off, disappeared into the distance, and darkness swallowed England’s coastline. There was no going back now, and I felt a dull ache in my heart as we went below for a meal.

Our first day at sea was not too bad, but as the water became choppier, I began to feel queasy. I’d been told that seasickness usually passed in a day or two but, oh, how wrong that turned out to be at least for me. The Atlantic became increasingly rough, making it more and more difficult to navigate the corridors and stairwells. People were being sick everywhere and on one occasion, as I attempted to make my way up a spiral stairway, someone vomited on me from two decks above.

‘Shit!’ I heard someone mutter, and I couldn’t have agreed more. I would struggle to one of the water fountains in the corridor for sips of ice-cold water, which I thought might make me feel better, only to find that it, too, had become a repository for vomit.

‘I’ll bring you some saltine crackers,’ offered Barbara. ‘They’re supposed to help when you feel sick.’ I already knew that was what our pregnant cabin mate was surviving on, so I tried some. It might have helped some people but I was an exception. I remember going into a toilet cubicle on a day when the sea was particularly rough and being unable to sit on the commode because of the pitching and lurching of the ship. I kept flying head first into the door, each time almost knocking myself out. Eventually I grabbed at the toilet-paper holder, trying to save myself from further injury, but it came away in my hand and I crashed to the urine-soaked floor. There I sat, bawling my eyes out.

During the second day of the voyage, we were called for lifeboat practice: a nightmare. Those of us who were seasick had a dreadful time getting ourselves into the life-jackets and finding our allotted mustering points. It must have been far worse for the mothers: they had to hold their children while both were wearing those cumbersome jackets it looked almost impossible. Many of those women were German and could speak no English. I supposed they were asking questions about what to do and where to go, but no one seemed able to communicate with them. Where were their husbands? I wondered. Surely they had to take part in the exercise too. I saw one young woman, with a baby in her arms, fall down some stairs. She sat sobbing into the strangling life-jacket until someone finally came to help her. I vowed then that if there was another lifeboat practice on this voyage, I wouldn’t participate.

With seasickness still making my life a misery, I discovered that if I dressed early in the morning and made my way up to the highest deck, where it was freezing cold and windy, I could stave off the nausea, at least while I was in that semi-frozen state. Every muscle in my body, but especially my abdomen, ached from heaving and vomiting. Up there, I would find a deck-chair and wedge it in such a way that it wouldn’t slide around. Then, bundled up in my winter coat and a blanket, I’d stay huddled for as long as possible, breathing in the frigid air. As soon as I went back below, the gut-wrenching nausea began again, and I remember thinking what a blessed relief it would be if someone tossed me into the churning sea anything to escape the agony.

Bob joined me when he could. ‘Come here, sweetheart, let me hold you,’ he’d say, as he wrapped me in his arms and tried to comfort me, but nothing took the nausea away. At night, I would swallow a double or triple dose of Dramamine, curl into

a ball on my bunk, and eventually drift off into dreams of the nights I’d spent on a similar bunk in an air-raid shelter during the war, while bombs fell all around us.

It was on the seventh day of the voyage that the weather improved: the sun came out and the sea calmed. I could walk about without fear of being flung against walls or down stairwells or, worse, swept overboard. Life aboard ship became bearable. Our Atlantic crossing took ten days and I felt fairly well for the last few and even managed to enjoy the experience. My three cabin-mates were pleasant girls. Barbara McCarthy, who insisted we call her Bobby, and I became close friends, and remained so for many years, in spite of my early reservations about her being too posh for me. I was thrilled to learn that she, too, was heading for Chicago. Throughout our friendship, Barbara and I were glad to have each other; we shared many good times and were always there for one another, offering comfort and support through the many traumatic events that were to occur in our lives.

Bobby and I had many bouts of the giggles over our roommate Gladys: her size and shape meant she could hardly get herself up onto her bunk.

‘Give ooz a boonk oop, will ye?’ she’d say, and of course, we did, all the time laughing until we cried. Gladys’s husband, Arthur, was also short. He reminded me of a leprechaun and was probably the minimum size accepted into US military service. When we spotted him on guard duty, it was all we could do to stop ourselves laughing aloud: all you could see under his helmet were his enormous horn-rimmed glasses and two big ears sticking straight out. Poor lad, he reminded us of a chamber pot.

The four girls in our cabin were assigned to one of the ship’s officers’ tables in the dining room. It was far too nice to be called the mess we even had fresh flowers on our table each day. The food was superb and I was sorry to have missed the first seven days of such fine fare. The men at our table were great fun; they teased us unmercifully, mostly about our accents but particularly about certain terminology. In my scrapbook, I have a paper table napkin, often called a serviette in Britain, and the captain had written on it in large letters ‘THIS IS A NAPKIN’, then everyone at the table had autographed it. That was just one example of how the differences between American and British English caused confusion.

We saw little of our husbands during the Atlantic crossing. They were still officially in uniform and had duties to perform, including guard duty. We usually saw them for two or three hours each day and on one or two evenings if they weren’t working. With so many newly married couples on board, a great deal of hanky-panky went on in remote corners of the decks and corridors. It was not unusual to turn a corner and run smack-dab into someone’s moment of passion; I often wondered how people could do ‘it’ standing up. The small cinema on the ship showed films until the wee hours each night, and when the lights dimmed, there was more lovemaking in those seats than appeared on the silver screen. Perhaps limiting contact between couples was supposed to rein them in. It didn’t work. I wasn’t interested in making a public spectacle of myself, but then, I was just a baby in that department. I was happy enough with a cuddle and remembering what had happened between us during our honeymoon in London. I could hardly wait to get back to the warmth and closeness we’d enjoyed then, and afterwards in our room at Mum and Dad’s house.

As our voyage neared its end, our excitement grew. We newcomers to America could hardly wait to see the famous skyline of New York and its welcoming Statue of Liberty. It was as though the whole ship was holding its breath, just waiting for someone to announce the sighting of land. Unfortunately, we all missed it: it happened while we slept on that last night at sea and the announcement came over the loudspeaker at dawn.

Rising at that ungodly hour, I dressed with trembling hands, knowing we had docked in New York’s harbour. I knew that Bob must be as excited as I was but I had no idea when he’d be able to join me on deck.

As I stepped out into the frigid late February air, I thought, This is it. I’m in the land of the Doris Day and Fred Astaire movies and my new Technicolor life is about to begin. I just knew it was going to be full of vibrant colour, unlike the drab grey England I’d left behind.

I pushed my way through the animated crowd and wriggled into a spot at the ship’s railing, which I grabbed with both hands. Squinting against the bright winter sunlight, I scanned the harbour and skyline for something that would tell me I wasn’t dreaming; that we had in fact arrived in America. Then I saw it, the Statue of Liberty, recognized throughout the world as the symbol of all that this great country represented. Many of my fellow passengers cheered but I stared at her in silence, my heart beating wildly. I had seen black and white pictures of Lady Liberty before, in magazines and newsreels, but now I discovered she was green, and so much more beautiful than I had expected.

As I wiped away a tear, I thought of the oceans of tears the Lady must have seen since she’d become the sentinel at the gateway to the United States, as she watched the ships and their ‘huddled masses’ pass through the portal and into the arms of America, their Promised Land. She was silhouetted against the clear blue sky and the towering skyline of New York City, a breathtaking scene.

I must have looked a complete idiot, gazing in awe at the panorama before me. Until someone pushed in close behind me and rudely poked a finger into my gaping mouth. I bit down, hard.

‘Ouch!’ I heard, followed by my husband’s familiar chuckle.

‘I should have known it was you,’ I said. ‘Serves you right.’ He never could resist teasing me. If Mum had been there, she might have done the same thing: she often made fun of me when I daydreamed, mouth agape, ‘Catching flies,’ she’d say, and called me Dilly Daydream. Suddenly, I missed her and my heart lurched, but there was no time for that now.

‘Come on, honey, you can’t stand there all day. It’s time to make sure we have everything packed and get ready to go ashore.’

This is it, I thought. This is really it.

3: New York

We said our goodbyes to the USS General R. E. Callan and its crew, waving at them as we disembarked. Then, herded aboard ferryboats, we crossed the bay to a different pier. On the way, we passed close to the Statue of Liberty. She was enormous and, quite simply, magnificent.

At our next landing place, we entered a huge building, which I believe might have been part of Ellis Island. Still on wobbly sea legs, my heart pounding and my stomach in a knot, I stood in line with the others, waiting for clearance through Immigration and Customs. A girl behind me began cow-like ‘mooing’, and then another joined in. Soon we were all laughing, which helped to ease the tension.

Once that tedious process was completed, military personnel ushered us towards waiting buses, which transported us to a hotel in the city where we were to stay while our husbands were processed out of the army and back into the United States. Hooray, I thought. I get to sleep with Bob again. I was like a wide-eyed child at Christmas as we rode across town, seeing all the huge cars in so many different shapes and colours. I craned my neck to glimpse the tops of the skyscrapers and then there it was, just as I’d seen it in movies and magazines, the Empire State Building, just as spectacular as I’d expected, even without King Kong’s giant gorilla climbing up it. I mentally planned a trip to the top before leaving New York.

When we arrived at our hotel, someone showed us to our rooms. Compared to the cramped quarters we’d endured on board ship for the past ten days, this was pure luxury. Bob turned up a few minutes later. We slammed and locked the door, grabbed each other’s hands, jumped up and down with excitement (well, I did), then melted into each other’s arms.

‘At last,’ he gasped. ‘I don’t think I could have waited much longer.’

‘Me ne

ither,’ I croaked, and he held me tightly to him. It was our honeymoon all over again.

Later that evening, I discovered that an American friend, Mary Lou Loy, whose husband was in the same unit as Bob, was in the same hotel. I had forgotten they were on the ship with us, perhaps because I had been ill for most of the voyage. I was delighted when she offered to take me under her wing while we were in New York and our husbands dealt with their army obligations.

The next day I was ready to see the sights. The men had to check in at the army base early that morning, so we girls had a late breakfast, then went off to explore the Big Apple. Fortunately, the hotel was within walking distance of almost everything we wanted to see, including the Empire State Building, Times Square, Radio City and all the department stores. We had two or three days in New York and I wanted to squeeze in as much as possible.

As Mary Lou and I strolled around the streets, I felt as though I had somehow landed on a movie set. I didn’t know where to look first. If I had been an electrical circuit board, I would have gone into overload and blown a fuse. I had to keep reminding myself that it was not a dream and I really was in one of the most famous cities in the world. Little Iris Jones, the council-house kid, was in New York City, USA. Wow!

Besides sightseeing, shopping was high on my list of priorities and that was where I got into the first of several embarrassing situations. Before leaving England, I had purchased a traditional English tweed skirt, one that would go with everything, of course.

‘Would a nice dark brown jumper go well with this skirt, Mary Lou?’ I asked. She laughed. ‘You mean sweater,’ she replied.

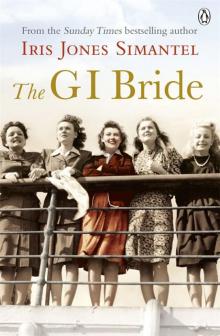

The GI Bride

The GI Bride