- Home

- Simantel, Iris Jones

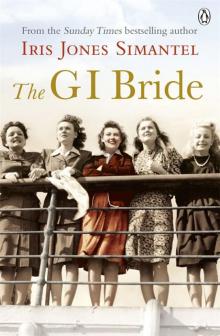

The GI Bride

The GI Bride Read online

Iris Jones Simantel

THE GI BRIDE

Contents

Foreword

1: Looking Back

2: Voyage to America

3: New York

4: Chicago and the In-laws

5: A World of Contrasts

6: American Firsts – Apartments, Job and Pregnancy

7: Our Baby, Motherhood and My First Visit Home

8: Back in the USA – Family, Friends and Independence

9: The Questionable Gift of American Citizenship

10: Divorce, and Home for Christmas

11: Single and Alone

12: Enter Robert Lee Palmer

13: The Palmer Saga Begins, and Meeting a Royal Butler

14: The TBPA and Convention Capers

15: New Baby and Las Vegas

16: Las Vegas, City Without Clocks

17: Chicago and Another New Job

18: Back in the Old Neighbourhood, and Al-Anon

19: New Neighbours and Unusual New Friends

20: Another Divorce and the Aftermath

21: Strange Encounters, and Life after Palmer

22: The Safety of Married Men

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

PENGUIN BOOKS

THE GI BRIDE

Iris Jones Simantel grew up in Dagenham and South Oxhey, before moving to the US with her GI husband Bob at the tender age of sixteen. She now resides in Devon where she enjoys writing as a pastime. Her first memoir about her childhood, Far from the East End, beat several thousand other entries to win the Saga Life Stories Competition.

To the more than 100,000 GI brides who left their homes and families to follow their hearts, but especially to those brave young women who fought loneliness, discrimination and disillusionment.

To the parents and families left behind, who didn’t know if they would ever see their daughters again. Some never did.

To the Transatlantic Brides and Parents Association (TBPA), founded by the families of GI brides to support each other in their longing for daughters who lived across a vast ocean. The TBPA also championed affordable travel between America and Britain by sponsoring charter flights between the two countries. It subsequently formed American chapters to enable previously isolated GI brides to form a supportive sisterhood. The organization remains strong and continues to support many British ex-pats.

Together Again is the title of the TBPA magazine, and that was what we daughters and our parents hoped and prayed we would be: together again.

Foreword

It is 16 February 1955 and I find myself, at the age of sixteen, one of hundreds of British and German ‘GI brides’, about to embark on the journey of our lives. We have all said goodbye to our families, homes and countries, to travel halfway around the world to begin a new life with our American husbands in a country we have only seen or heard of in movies or on television. Is everyone as frightened and excited as I am? What can we expect in this strange new world? Will we be welcomed? Will I ever see my family again? What if I’ve just made the biggest mistake of my life – or are all of my dreams about to come true?

All of these questions, and more, crowd my mind as the USS General R. E. Callan begins its long voyage across the Atlantic Ocean. There is no turning back now: in a matter of days, I, with all the other apprehensive GI brides, will set foot on American soil. Our new lives will begin. How had I, a mere child, many thought, arrived in this place, at this time? How had this journey begun? And how will it end?

1: Looking Back

Life had not been easy for me in England. It had begun when my mother almost gave birth to me in the toilet and, in some ways, it didn’t improve a great deal after that.

I was born into poverty on 5 July 1938, in the East End of London. My parents were living temporarily with my grandparents in Station House on Blackwall Pier, where my grandfather was the stationmaster. The pier, Brunswick Wharf and the railway station were part of the East India Docks on the banks of the River Thames in Poplar, which is situated within the sound of the famous Bow Bells, at the St Mary-le-Bow Church. According to The Victorian Dictionary, ‘Only those born within the sound of Bow Bells are properly called Cockneys.’ I was not always proud of my Cockney label and heritage: to the upper classes, the term suggested indolence, dishonesty, illiteracy, lack of manners and absence of personal hygiene. That label, and the tell-tale accent, defined a Cockney’s station in life and served to trap them in an often cruel, discriminating world.

My older brother, Peter, and I were born in peacetime Britain, but that peace was soon shattered when war was declared against Germany in 1939. My earliest memories are of air-raid sirens, anti-aircraft guns and bombs exploding; worst of all was the sound of my mother crying. In my fright and confusion, I would crouch in a corner, to hide my own tears. At night, we hunkered down in our air-raid shelters, feeling the earth shudder beneath us as bombs landed nearby. Afterwards, we often had to wipe away the dust and dirt that filtered through the cracks in the corrugated-iron roof. Filled with terror and wishing my mother would hold me close to her, I often cried myself to sleep, wondering what it would feel like to be blown to pieces by a bomb.

My mother suffered a series of nervous breakdowns during those years, and my father was a physical wreck from working at the Woolwich Arsenal, which was bombed almost nightly, and from continuous nights on fire-watch duty. I have no doubt that the physical and psychological illnesses people experienced at that time were greatly exacerbated by sleep deprivation and inadequate nutrition.

Peter was one of the first children to be evacuated out of London in what the government called ‘Operation Pied Piper’, the scheme to keep Britain’s children safe. Because I was younger, I wasn’t evacuated until much later: Germany had developed unmanned missiles, the V1 and V2, that were about to be deployed in a new nightmare of attacks.

My family spent the war years wondering if we would survive, or if we would ever see each other again. We could only wait and hang on to hope. My brother and I had different experiences at our wartime billets: Peter’s was not happy but I was lucky enough to be taken in by a kind family in South Wales. The local children ignored me when I first arrived in the coal-mining town of Maerdy, but although I was lonely, I made happy times for myself, playing on the beautiful mountainsides of the Rhondda Valley. Luckier than many other evacuees, I had plenty to eat and was well cared for. It broke my heart when I had to leave my Welsh family to return to the family I had begun to forget.

My family all survived the war, but I believe we came out of it with scars, not necessarily physical – although my father had many from his work at the arsenal – but emotional. They stayed with us throughout our lives. When Peter and I returned to our parents after the war ended, we found it hard to readjust to each other. For a while, we were like strangers in our own home, and I know my mother had a difficult time dealing with us. We were not the same children who had left years earlier when we were just five or six years old. Our parents were different too: the war had changed them. There seemed to be an invisible wall between my mother and we children, which seemed to strengthen when, in late 1946, she gave birth to a third child, our brother Robert. As soon as he arrived, he demanded almost all of Mum’s attention, and she slipped once more into depression. Perhaps it was what we now call post-natal depression, but I learned that it had much

to do with my father’s habitual philandering.

Approximately two years later, as the memories of war faded, London’s poor were encouraged to move out of the city, to enable the clearing and rebuilding of the slums and bomb-damaged areas. The government offered brand new houses on newly built London County Council (LCC) housing estates, located mostly in rural areas. Many Londoners refused to leave the city, but when we were offered the opportunity, Dad seized it. He decided we would have a better quality of life if we moved away.

On 1 May 1948, the Jones family trundled off in a borrowed truck, loaded with all our worldly possessions, and headed for the South Oxhey estate, which was near to Watford in Hertfordshire. We were met with a troubling situation: the houses were new, modern and inviting, but with little of the infrastructure of the new town in place, we all wondered how we would survive. The houses sat in a sea of mud and building detritus; there were few roads and no pavements, schools or shops. We looked at one another, each of us thinking, What’s Dad got us into now? Our new life was about to begin, and at that moment, we all dreaded it, none more so than poor Mum. I can still hear her saying to Dad, ‘And they call this progress?’

For us children, life in the countryside, in spite of the mud and lack of amenities, was exciting. There were fields and woods to explore, berries and bluebells to pick, trees to climb and camps to build. Even Mum seemed to relax a little. She made us all laugh one morning when we awakened to find that cows from a nearby field had trampled down our flimsy fence and were wallowing in the garden. ‘Blimey, them’s big sparrows,’ she said. It was wonderful to hear her make a joke because it didn’t happen often, especially in those early post-war days.

It was fun taking the bus to school in Watford, even though we were not welcome there. The local people didn’t want us so-called ‘dirty Londoners’, and we suffered a great deal of derision and discrimination. That changed when we were provided with our own schools and the rest of the amenities we needed to be independent of their precious resources. I felt much happier when I discovered that my best friend, Sheila McDonald, had also moved with her family to the new estate neither of us could believe our luck.

Mum had never seemed happy. She battled constantly with depression and was never able to show me the affection I craved. As a family, we were always trying to make her laugh but she’d usually tell us to stop mucking about. When I tried to get close to her, she pushed me away, telling me to stop bothering her. It was worse after she gave birth to my youngest brother, Christopher, and once again fell into a deep depression. This time it was so bad that she went away with the baby to convalesce, leaving me, at the age of twelve, to take care of the family. I loved being woman-of-the-house. For the first time ever, I felt wanted and needed, but when Mum came home, I was invisible again.

In my early teens, I began to spend time with some fun-loving young neighbours. From them, I received an extremely colourful sex education; my mother never talked about sex, and certainly not to me. She was too embarrassed to buy sanitary towels; she simply used pieces of old rags, which she laundered and reused. Of course, I knew nothing of this: she was good at hiding the things she didn’t want anyone to know about.

During our early years in South Oxhey, my father worked at Odhams, the printing company, in Watford. He was instrumental in starting the estate’s first Sunday school, perhaps trying to mend his philandering ways. When that affiliation ended, he joined the Watford Spiritualist Church and was soon involved in healing and clairvoyance. He became increasingly popular and respected in the world of spiritualism, and was eventually president of the church. He spent more and more time away from home, while Mum became increasingly withdrawn. She wanted nothing to do with the church and wouldn’t join in when Dad wanted to talk about it so I became Dad’s audience at home. I loved listening to him: at last, someone was paying attention to me. He and I drew closer, but that, I believe, drove a bigger wedge between my mother and me. She was jealous, and if I’d thought she didn’t like me before, I was sure of it now.

When I reached fourteen or fifteen, I began dating. According to Mum, I was boy crazy, and she told me off endlessly. I talked back to her now, telling her that at least someone was paying me some attention because she certainly wasn’t. ‘What do you want from me?’ she’d shout. I’d tell her that a few kind words would be nice. She would turn her back and walk away, shaking her head as though I’d asked for the impossible.

Yes, I went out with lots of boys, and sometimes young men who were far too old for me, even though I was soon tired of fighting off their demands for sex. I was also fed up with insults about my virginity. But just when I’d decided that my mother and grandmother were right when they claimed that men were after only one thing, I met my Mr Wonderful. Not only did he prove them wrong, he brought a ray of sunshine into my life, which began to change.

I’d been to the cinema with a girlfriend and we were on our way to catch the train home when we heard someone call out to us. Two American soldiers asked us for directions. Neither of us wanted anything to do with American servicemen because girls seen with them were called ‘Yanks’ meat’. No one with any self-respect wanted that label attached to her. We tried to ignore them but we were finally convinced that their intentions were honourable: they really needed directions. Well, one thing led to another: they ended up taking the same train as us and then they walked us part of the way home. We talked until the street lights went out, leaving us in the pitch dark, and we still hadn’t given them directions back to their base. It was after midnight by now and my friend and I knew we’d be in big trouble if we didn’t get home soon. We scribbled directions on a piece of paper and off they went.

At that time I was just fifteen, had recently left school and was working in a dress shop in Watford. There was no way I wanted to get involved with American soldiers and I didn’t think they’d be interested in me. I assumed they were after the older girl I was with, but she was less interested even than I was because her father was an abusive brute he would have killed her if he’d found out she’d been talking to them. As it happened, he gave her a black eye for being out late, then threw her and her clothes out into the street.

The only thing my mother worried about was what the neighbours would think about me coming home late. She would have been mortified if someone had seen me talking to Americans.

The next week I was putting new stock away in the shop when the manageress called me into her office and told me there was a telephone call for me. I was shocked and thought it must be a mistake, especially since I didn’t know anyone who had a phone. I was even more shocked when the caller turned out to be the good-looking American soldier I had met the previous weekend; he wanted to take me out on a date. I was almost speechless. He explained that he had remembered where I’d said I worked and had looked it up in the phonebook. My God, I thought, he’s either desperate or actually interested in me. I knew I couldn’t talk to him for long on the phone so I agreed to see him the following Saturday. Until then, I had to keep it secret from my parents and control the butterflies and palpitations that stayed with me for the rest of that week.

At last Saturday arrived and I wondered if he would turn up. He did. He was waiting for me outside the shop when I finished work. We grinned like Cheshire cats, and although we had planned to go to the movies, we never did. We had dinner at a little café and talked until it was time to catch the last train home. His name was Bob Irvine, and not only was he a perfect gentleman, he was funny and kind. Above all, he treated me like a real lady. He asked if he could see me again and I told him I’d have to think about it because I knew my parents wouldn’t approve. I asked him to phone me the following week. I also explained t

hat we had no phone at home and that he would have to ring me at work. He was shocked that anyone could still be without a telephone, but he hadn’t been in England long enough to learn of the many differences between our two countries.

After one or two more dates with Bob, I mustered the courage to ask my parents how they would feel if I invited a young American soldier home for Sunday tea. Eyebrows shot up, mouths flew open, and I thought that the house and my parents might explode. The inquisition began. How did I know an American soldier? What was I thinking? Was I insane? And, of course, an unspoken question hung in the air: what would the neighbours think?

Where we lived, it was almost impossible to avoid meeting Americans. Their military bases surrounded Watford. There were air force bases at Bovingdon and Ruislip, and an army base at Bushey. I believe there were then as many as twenty-four US bases in southern England, and most of the young men and women stationed there were serving their mandatory two years’ national service; they were almost all single and undoubtedly ‘feeling their oats’. The Second World War might have been over for seven or eight years but the American presence in Europe was still strong.

In the 1950s the attitude to American service personnel in England had changed: during the war years, I don’t believe young women who went out with ‘Yanks’ had been stigmatized as they were now because most eligible young British men were away fighting. The war had brought new priorities: civilians as well as the military were at risk of losing their lives and everyone seemed to grab what joy they could. When peace came, young British men resented the American presence and their perceived domination in the area of dating; they didn’t think they stood a chance against the Yanks with all their money, charm and confidence. Most young Englishmen were serving or had just completed their own mandatory national service; they had far less money to spend on girls. ‘Yanks’ meat’ implied that those girls were selling themselves to the higher bidder. I hated the thought of acquiring that label, but what can you do when Fate steps in?

The GI Bride

The GI Bride